Compass

It was in the middle of summer and I was sprawled on a grey-green couch in Queens. My clothes lay in a heap near a glass table, my companion's black bra and shorts by my feet. She lay on top of me, licking my breast, teeth pressing down every so often in a mixture of pleasure, pain and some cool sensation between both. I kept apologising as my nails dug into her back.

I felt amazed each time she applied pressure to my nipples. I’d had many sexual partners – most of them cisgender men – do things with my breasts, but never like this, even as the basic method seemed the same. The quiet shock-sync of enjoying each other, of wanting not just the contact of bodies but our bodies. To be sure, sex with someone you care for feels different, higher, more incandescent, and I already knew this was someone I liked as more than just a casual companion. But it seemed like something simpler, too: that I was realising my body was more capable of pleasure than I’d ever imagined.

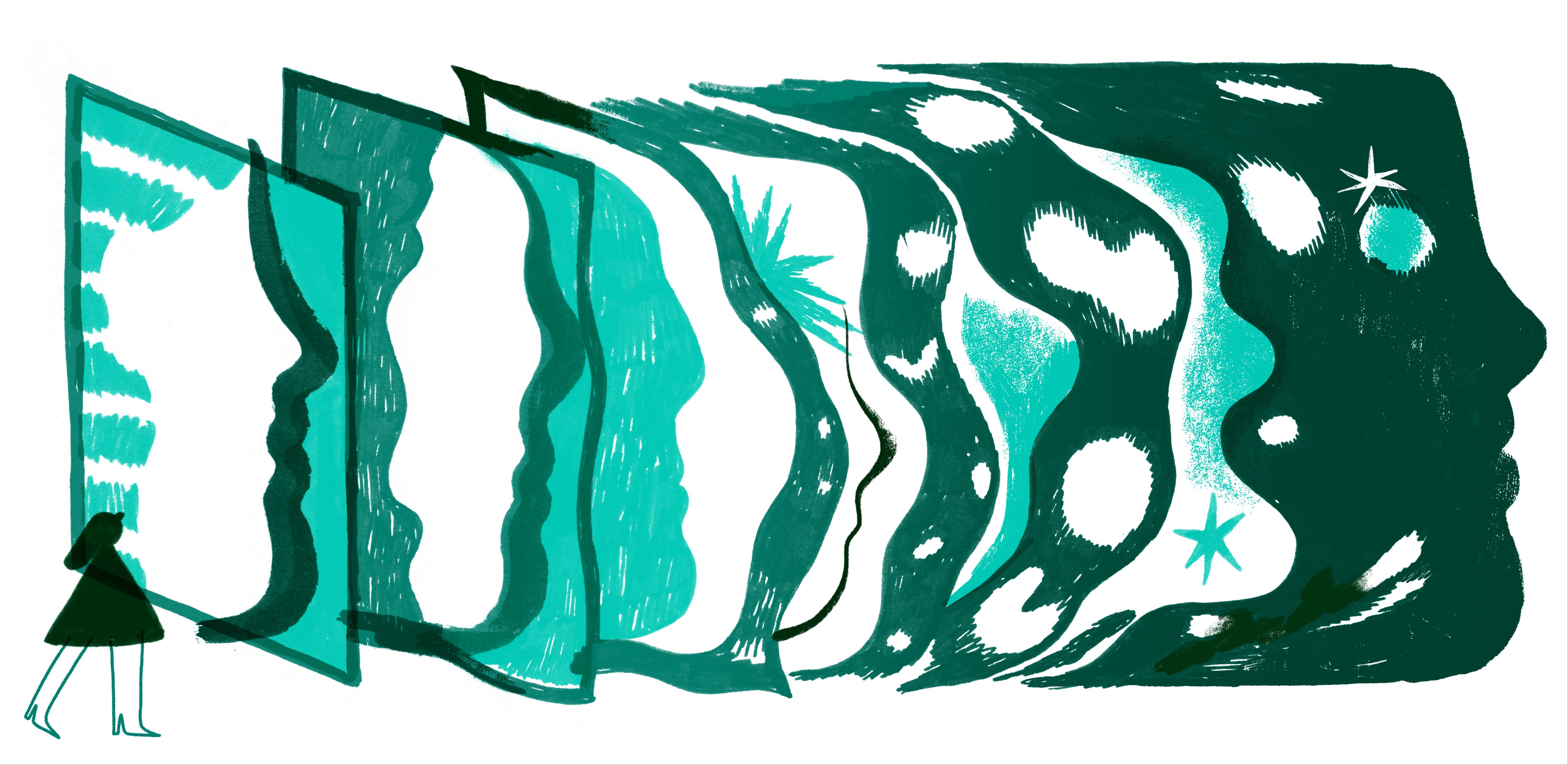

As a trans woman, this revelation was important. For so long after coming out, I both expanded and contracted my corporeal and sexual horizons, experiencing new joys (like being fucked by men and sleeping with a woman while being perceived as a woman myself) and new pains (like my fear that my genitalia instantly made me less worthy of womanhood than a cis woman). I loved the idea of being desired by people, which made even crude behaviours like catcalling occasionally seem welcome early in my transition; for all their crassness, comments by men who found me attractive, or attractive enough, felt in weak moments like validation of my ‘passing’ as a woman. I loved when my sexual partners told me my body turned them on. Yet I constantly told myself in private that a body like mine could not really be desirable, simply by virtue of my sex not corresponding, in my mind, to my sense of gender. That I also had stretch marks and a voice that, for a long time, seemed unable to 'pass' increased my anxiety about my body, until it felt as though the sea-compass of myself was spinning, wilder and wilder, and I lost all sense of direction, floating aimlessly instead on the grey of depression.

Shortly before the start of a new millennium, the lesbian activist Sheila Jeffreys published an article in the Journal of Lesbian Studies, which argued at multiple points, and with a tone implying that her points were simply common-sense assertions, that transgender people were a pressing danger to the queer community. So unsettling were trans people, indeed, that she declared in this 1997 jeremiad that transsexualism – the common term of the era for transitioning – was a ‘violation of human rights’, a phrasing so inflammatory and extreme that it has become one of the few things people know about Jeffreys today, if they know who she is at all. Even at the time, the 1990s, her depiction of trans people was shortsighted and callous. By then, a few trans individuals had already captured the public imagination, if fleetingly.

One of the earliest of these appeared a few years after the conclusion of the Second World War. In 1952, a veteran named Christine Jorgensen had become arguably the most famous trans woman in America – if not the world at large – when the press announced her transition in sensationalist headlines. ‘Ex-G. I. Becomes Blonde Beauty,’ the New York Daily News announced. She had undergone reassignment surgery, then still a relatively inchoate set of procedures largely unfamiliar to the general public, and the seeming novelty of her story gripped America. After the Second World War, America – already a hub of technological innovation – had positioned itself even more strongly as a kind of technocratic powerhouse where any and everything might be possible, and Jorgensen’s transition, to some Americans, represented that drive. A body could, through the marvels of new medicine, shift its sex; Jorgensen, in this view, was at once transgender (or, in the parlance of the day, transsexual) and an embodiment of the idea that science could do just about anything.

Initially, media reports described her, progressively, with female pronouns. But when Jorgensen revealed that she couldn’t menstruate or become pregnant, a number of publications reacted by switching to male pronouns and condescended to her, as if to imply that she had deceived them. If she was not completely indistinguishable from a generalised notion of a cis woman, the thinking went, then she could not be a woman at all; she was merely a duplicitous, liminal being, stitched together into the semblance of a thing but unable to ever fully be that thing. Jorgensen began to fade from the public eye, but she was soon replaced by tennis star Renée Richards, who rose to fame when she fought to compete in the Women’s Open in 1976 after also undergoing reassignment surgery. She won that right in 1977, when a judge ruled that ‘[t]his person is now a female’, a decision that helped once again spring a trans woman into the national – and international – spotlight. Although both Jorgensen and Richards attracted controversy and frequently had their womanhood questioned in the mass media, they also, along with other trans or gender-non-conforming pioneers like Marsha P. Johnson, helped shore up some visibility and support for the trans community. This was twenty years before Jeffreys's characterisation of transitioning as a human rights violation.

The present is less different from Jeffreys's era than most hopeful liberals might wish to believe. Her fear-mongering about trans individuals has become a mere precursor to the alarming and alarmist rhetoric of the Trump administration today, from President Trump’s attempt to ban trans people from enlisting in the military to the more recent revelation of a leaked memo proposing widespread legal erasure of rights and acknowledgement of trans people. The memo, proposing that we would be legally defined solely by our genitalia at birth and making it impossible to change gender markers on legal documents, is a proposition to make us cease to exist legally.

Even as a cultural pendulum has begun to swing a bit more in our direction – at least in more liberal parts of the country – it’s still unsurprising to hear that pushing for our rights to exist in public or even in private is a step too far. That trans people are too weird, too different, too dangerous to both others and ourselves in bathrooms and bedrooms alike. That to allow – such a telling choice of verb – kids who consistently self-identify as trans to begin to transition is tantamount to child abuse – even though forcing us to go through the often irreversible body changes of puberty is itself lasting and painful in a way few cisgender people could ever imagine.

*

One afternoon when I was in secondary school, I remember deciding to go down into a valley-like area in our yard where many of our most bounteous plants grew – breadfruit, grafted mango, lime, guava, pineapples, coconuts, a much-maligned coffee plant whose products never pleased my mother and which confirmed her lifelong belief that Dominica’s coffee was not as good as coffee almost anywhere else in the world. I often explored the little valley with our German Shepherds, who loved nothing more than to chase terrified anoles and skinks through the large rotting breadfruit leaves, and with admirable effort and ingenuity rip apart hard brown coconuts to get at what little meat and water might be left inside. The valley was a place to disappear for a bit, both from my parents and into my head.

I walked over the crisp browned breadfruit leaves lying on the grass like curled, withered things that had once been gargantuan bats, and I had a clear vision: I was a tall woman, hair wrapped in multicolour cloth. I thought of walking into Jolly’s Pharmacy in Roseau, our capital city, and buying one of the white tubes of generic lip balm (my mum forbade me from using lip balm for many years, as she thought it too effeminate) or one of the black pressed powder compacts or even just something mundanely unisex. I imagined doing the most mundane things as a woman. Sometimes, I stood out in these visions; other times, I was an unremarkable girl lost in the tarp-flutter of a crowd.

But I was afraid that if I acted on my urges to live as a gender distinct from my sex, I would go to hell, as the priests declared in church on Sundays. I barely even understood what it meant to feel that I was a girl when everyone called me a boy; I imagined, at times I might be hearing the seductive words of Satan in my ears. The music all my friends danced to reinforced the understanding that queerness of any kind was infernal – in particular the American hip-hop and Jamaican dancehall songs with lyrics that frequently alluded to beating the shit out of ‘faggots’ and ‘batty boys’ and ‘trannies’. I feared someone would do the same if they so much as suspected I was queer.

So I tried to suppress my feelings. I tried dating girls as a teenager. And I did, but it never felt right. I didn’t want to act like ‘the man’ in our relationships, even as I postured as one on the surface as roughly as I could. I wanted, instead, to walk out the door and we would both be wearing the same jeans, hand in hand, hair flying in the breeze, t-shirts tight over our breasts. I never said any of this, so I just came across as awkward, made the worse by my natural shyness. Unsurprisingly, my relationships didn’t usually last long.

*

Sex seemed a cloud-thing, there and yet distantly out of my reach. I wanted something that seemed impossible: to be the woman in my visions, my arms and legs entangled in another woman’s, or held by a man’s. When my libido dimmed, I still saw myself as the woman I envisioned, going out to a store to buy groceries and perfume, or venturing out to festivities with imaginary friends who, in this parallel universe in my head, had always known me as female; if anything, I wanted to be this quotidian ghost more, wanted to walk in her shoes every day, every moment.

I wondered why she resided in my skies. I wondered if it was some cruel temptation from a biblical devil or some curse for a crime, like original sin, I had not committed but was made to suffer for all the same. I wondered if I was merely mad. Twice, the woman in me brought me near to suicide: once, before coming out, when I was so unhappy being perceived as male; and a second time, when the weight of the new pain accrued after transitioning – my mother unable to accept me as her daughter rather than her son, my rejections by dates due to my body not being a cis woman’s, my loneliness – became too heavy to bear. Yet, for all that, I would never want to live any other way than as the woman I am.

I have often wondered what my life would have been like if I had never been forced to go through male puberty. If, in some ineffable parallel universe where queer people were accepted, I could have been given puberty-blockers and hormone therapy (or had simply been born a cis girl) to let me go through my teenage years as a girl. My college years, the first half of my years in graduate school. I wonder, too, if I could be me at all, without the scars of all those years of depression and discombobulation. If I could be me at all, without having come so close, all those times, to self-annihilation.

*

The question of whether or not trans women should be included in events or spaces simply for ‘women’ – which should not be a question any more – created many controversies in feminist circles, particularly from the 1970s onwards. In 1973, the West Coast Lesbian Conference in Los Angeles erupted into controversy over whether to allow Beth Elliott, a trans folk singer, to perform. The keynote speaker, Robin Morgan, indignantly argued that her ‘thirty-two years of suffering in this androcentric society’ made her a woman and inquired how a ‘transvestite . . . dares understand our pain? No, in our mothers’ name and our own, we must not call him sister.’ The Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, founded in 1976 by Lisa Vogel and having catered to thousands of women each year until it shut down in 2015, notoriously billed itself as a venue only for cis women – ‘womyn-born womyn’, as Vogel put it. To let trans women in, Vogel declared on many occasions, would make cis women uncomfortable, rather than ‘allow[ing] women to let down their guard,’ and Vogel repeatedly denied that such exclusions were ‘transphobic’ in any way. The annual RadFem Collective conference routinely excludes trans women from participating, despite being billed as a space for women to discuss women’s issues. For years, the famed feminist Germaine Greer has courted controversy for blithely claiming that trans women are ‘not women’ because we do not ‘look like, sound like, or behave like women,’ as she informed the BBC in 2015. The Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie made headlines in 2017 when she argued that ‘women’ should be separated as a category from ‘trans women’ because trans women, supposedly, lacked the ‘universal’ experience of girlhood that all cis women had in Adichie’s mind. We, ergo, were irreparably, if not unbridgeably, different in some way at the end of the day. Separate but equal – and how ironic for a black woman who, like me, is a child of British colonialism, to reproduce this familiar genre of prejudice.

This argument – that we can never really be women because our experiences being socialised might be different from that of cis women – is not unlike the us/them binary of colonial rule. Colonies were places that needed to be fixed, improved, changed in some way to be acceptable – even if it was clear that those from the colonies would never really fit in with those from the Mother Country. It is sad that those who have railed against the false logic of ‘separate but equal’ could in turn impose the same rhetoric against different groups – like trans people – they do not understand, nor wish to.

You become accustomed, when you’re trans, to thinking that you don’t belong. That genders are their own isles, and you can never cross over. You become accustomed to feeling that you will never fully fit in, even if you avoid shipwreck.

*

To be with anyone before coming out is different from being with them after. Your body changes, both from hormone therapy and from you now being you, a place of new possibilities. Transitioning, after all, is never solely about the subtle changes it makes to our fat distribution, body hair, breast growth. If you’ve wanted to be seen as a woman all your life, having sex with someone who accepts – sees – you as one feels utterly remarkable, not simply on a physical level, but an existential one.

You feel right, suddenly – despite any lingering dysphoria. While I still struggle with whether or not I am comfortable being touched in the place where I wish a vagina was – a struggle that may never disappear so long as my genitalia remain what they are – I have accepted my womanhood in a deeper sense. Nothing taught me how many ways there are to tease pleasure out of my body, or how malleable, multifarious, and vast sex can be, better than transitioning.

When I lie again on that lovely couch in Queens, and hold that same woman’s head against my breast as we drift off to sleep together, I think about how long I’ve waited to feel desired, not only sexually, but in all its senses. How surreptitiously, suddenly, desire entered my life. Having drifted away on the vessel of a couch or a bed or a walk with someone by my side, I had found something like a safe harbour.

Gabrielle Bellot is a staff writer for Literary Hub. She grew up in the Commonwealth of Dominica. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Atlantic, Shondaland, Guernica, Slate, Tin House, The Paris Review Daily, The Los Angeles Review of Books, New York Magazine's The Cut, VICE, The Normal School, Electric Literature, Lambda Literary, The Toast, TOR.com, Caribbean Review of Books, Small Axe, Autostraddle, the blogs of Prairie Schooner and The Missouri Review, and elsewhere.

Made in Heaven

January, 2019

On transcendence in two essays, a short story and four poems. Featuring illustrations by Franz Lang.