The One and Only

Infatuation is a solitary pursuit. Dante doesn’t want to be with Beatrice: he wants to be alone. In his 1225 libello, La Vita Nuova, Dante describes what he does when he sees Beatrice on the streets of Florence: ‘I withdrew from people as if I were drunk, away to the solitude of my room, and settled down to think about this most graceful of women.’

A real Beatrice stands with real desires on a real street in a real city in real shoes. This is inconvenient to any Dante. Any actual Beatrice’s opinions on the weather or local politics would inevitably be mismatched to ‘the glorious lady of my mind’ – the Beatrice of Dante’s room.

Dante locks himself away and falls into a fugue that has nothing to do with Beatrice herself, but everything to do with the generative possibilities of the feeling of having seen her. Dante sees Beatrice at nine in the morning. By four in the afternoon he is having a vision in red silk and writing a poem for all who are, like him, besotted.

The imagined Beatrice is completely in Dante’s control even as he believes he is in hers. Any Beatrice is an accident, with the effect of an ulterior Beatrice for which the real Beatrice is not to blame.

*

*

Seduction’s speeches often involve ardent declarations that the beloved is the one and only. This is not because the beloved is really the one and only worthy of love; instead, ‘the one and only’ is a linguistic betrayal that the pleasure of being besotted, a pleasure of a plunging hyper-focus in which a person can be totally alone.

There is no room for that beloved to exist simultaneous to the feeling about them. The beloved as a plurality – idealisation, actual person, future and past person – is far too big of a crowd for infatuation’s room.

As Stendhal writes in his 1822 book De l’amour: ‘It should be remembered that a person under the stress of strong emotions seldom has time to notice the emotions of the person causing them.’

*

It’s not so bad to be Dante, but it’s generally no good to be Beatrice, who never gets to talk and would never be listened to even if she did. It doesn’t require much but existing semi-attractively and in public view to become a Beatrice. One day you wake up a person, but by 9 am you are the site of someone else’s erotomaniacal accident. Your new identity is Beatric.

The Internet makes it worse – an algorhythmic Florence in which we never know when our presence passes through the sight of someone in need of a distraction from looking at the world. To be put in a Beatric position is a frequent accident of information, the vestigial capacity for impossible love inflamed by the not-there always-there-ness of social media. Some Dantes are content with keeping it to themselves, but others disinhibit and intrude, begin to stalk.

It is sad, even as it is stressful, that what could be generative – an epic crush – under current conditions of patriarchy and screen life and everything else wrong with the world becomes threatening, and like all such aggression, banal. I wrote an email about the woes of being aggressively Beatricised again to a friend with whom I was myself often in impossible and possibly-unwelcomed love: ‘Isn’t there a statue somewhere these people can fall in love with instead?’

*

I’ve been Beatrice. I’ve also been her opposite. I have needed a statue, too, as that time when the friend in question accidentally passed in front of my neediness and I believed myself in painful love. I am sorry / not-sorry about the love poems I then wrote alone in my room.

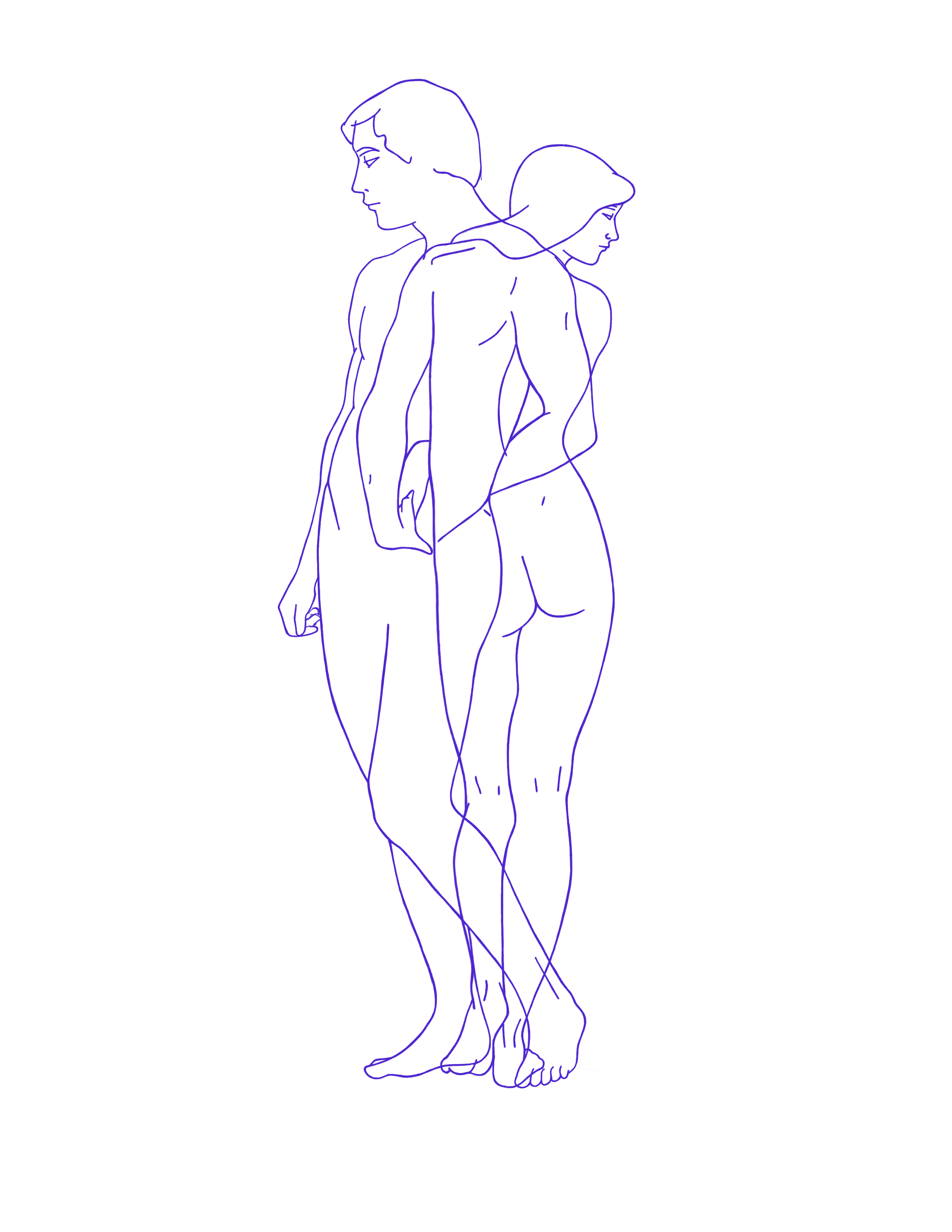

We could, perhaps, erect at least two statues built for unreciprocated and inventive loving. One could be called Beatrice, the other called Dick, after the uninterested male muse in Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick. Whenever the vital necessity of being in that deep solitude of only having eyes for arises, all that incomparable production of the imagination could be turned toward the worship of a Dick or Beatrice or some third, gender-defiant beloved as yet to be named in our common literature.

These statues would be sculpted, without ears, out of cool and unfeeling marble. Those with the poetic feeling of love that means staying home to fixate until art is made could have an appropriate target at which to direct their efforts. The statues would be perfect, too, because they could never talk, and any motion on their part would be as if a miraculous Marian-vision, in which the blessed virgins of our imaginative desires were collectively hallucinated into dropping a tear.

We could preserve the refuge of impossible love without asking anyone to endure the discomfort of having to be a beloved ever again. Imagine Kraus’s Dick, marble, earless, and wreathed in flowers, now crying as we stand in all our need and wonder.

*

The greatest catastrophe that can befall love is that someone admits it out loud. ‘I love you’ is almost always love’s malediction. Second to this catastrophe of declaration is the catastrophe of perception: a lover who can see clearly is a lover looking at the end of love.

To only have eyes for necessarily means to not see at all, or at least to only have eyes that look inward. The auto-generated phantasms of infatuation decorate an interior view more captivating than any of reality’s landscapes. Part of the pleasure of loving someone who can’t love you back or who you never bother to tell is to only have eyes for whoever or whatever as often and as widely as one wants, and to never have to have ears to listen to how anyone else feels about it. To only have eyes for is to leave any beloved unseen, to allow the unstated its full weight and power by never disfiguring want by offering that want to its object.

*

The young poet in Soren Kierkagaard’s 1843 novella, Repetition, is also a poet in love. Dante is lucky that Beatrice never makes the demand that comes with reciprocating his feelings. Tragically for the poet in Repetition, the woman he loves also loves him, and when the pleasurable pain of desire gives way to the looming threat of marriage, the poet wakes up each morning and tries to be what he is not. He attempts to transform himself into ‘a husband,’ to lay aside his ‘soul’s impatient and infinite striving’. No more able to make himself into a husband than to stop his own beard from growing, he prays for a thunderstorm. It’s a ridiculous prayer for a ridiculous solution to a ridiculous situation in a ridiculous book. Only a thunderstorm, he thinks, could make him happy. By destroying his whole personality, he posits, a thunderstorm could finally make him fit to be wed.

He had once been ‘deeply, passionately, self-effacingly’ in love, but love’s threatened culmination – domesticity – is the most annihilative thing he could imagine, one to be prepared for only by preemptive self-annihilation. The other worst thing that has ever happened to romantic love is marriage (closely followed by therapy), not least for constituting the surrender of erotic life to the obscene economies of reproduction. Kierkegaard’s poet only has eyes for love, which means that the beloved herself would crowd his view. The practical, socially sanctioned culmination of love would be an even greater affront to his vision.

When the poet’s potential wife decides to marry another, he is ‘handed intoxication’s beaker’. He loves his beloved all the more now that she has so generously decided to release him from love. Ecstatic, he once again devotes himself to the ‘idea’, allowing it alone to summon him, allowing his allegiance to thought to disappoint no one. He will no longer need to be distressed at distressing another. Repetition’s satirical close-call with de-idealisation and the actualisation of love should remain a lesson to anyone who, when it comes to love, is crazy about the pregnancy but horrified by the birth.

*

‘I came to Carthage’, wrote Augustine in his Confessions of the year 397, ‘where there sang all around me in my ears a cauldron of unholy loves. I loved not yet, yet I loved to love, and out of a deep-seated want, I hated myself for wanting not. I sought what I might love, in love with loving, and safety I hated, and a way without snares.’

The greatest danger of epic wanting is to mistake wanting to want with actual wanting. One must engineer the most durable delusion to sustain the state of totalising desire with unachieved and unachievable reciprocation. Some impossibility has to undergird that desire and hold it in place as long as it is needed. And if you have found the ideal circumstance of impossibility – say who you love is already in love with or otherwise committed to someone else, or does not know you, or is far away, or is dead, or is not interested in loving someone like you – you have found a perfect city of the fecund and perpetually realised unrealisable.

That durably built delusion is a place I think of, after Augustine, as Love’s Carthage. This Carthage is a city made of the desire for desire, in which no doors may be opened, in which all streets lead to more streets, in which all the citizens have hearts and mouths and grabbing hands but no one has eyes or ears. In this city, every lover sleeps alone in their room for the purpose of fantasising they are sleeping accompanied in someone else’s. All votes are cast in favour of future voting, as this is the way to perpetuate intention but never lay down the law. All trash bins are full of discarded sonnets, and all clouds are the condensations of tears.

*

An epic crush should be a mammalian right, unimpeded by gender, but imagine how much more difficult for the poet in Repetition had he been a she trying to transform herself into that even more annihilated annihilation, a wife. There is no romance yet, queer or otherwise, that can exist apart from the general tragedy of how we are, at birth and by gender, divided into two.

A poet who became a wife would not only have to be called away from thought’s flight by the necessity of dinner, she would probably have had to make the dinner and do the calling, too. The idealisation of love forced into its actualisation is merely a hilarious threat in Repetition, but it is a terrifying one if applied to the specific conditions of woman engaged in heterosexuality. Marriage, for women, is not only potentially deadening, but has far too often been and still is deadly. But people who aren’t men deserve to fall in foolish love, too, with whomever they like, and sink for years into that fugue of want that has, as its potential, most literature and almost all philosophy.

It is possible to make and support an argument for the epic crush and against its harmful, intrusive iterations and also against its culmination in a relationship – either marriage or its contemporary business casual form, the one in which the heart is understood to be a junior partner in a law firm – partnership. One of the most impressive iterations, then, of to only have eyes for with never having to also have ears has to be Emily Dickinson’s love for ‘the master’, enacted in a series of three mysterious letters written across the late 1850s and early 1860s, signed ‘Daisy’ and addressed to an uncertain ‘Sir’:

I want to see you – Sir – than all I wish for in this world – and the wish – altered a little – will be my only one – for the skies –

We learn so little about Dickinson’s ‘Master’ in her letters to him that he might as well not exist for what we are never told about him. Dickinson was wily about avoiding marriage or any other form of captive love while preserving her poet’s capacity to telescope her desire into solitary and crystalline iterations. It is possible that ‘the master’ of her letters, if he existed, was spared having to read the letters addressed to him. Dickinson could perform a literary self-effacement and avoid a literal one by effacing her beloved by her genius for enigma.

Any response by the master to Dickinson would have been rudely interruptive, too. I can think of no uglier literature than what anyone called ‘master’ might write in response to Dickinson’s master letters.

*

‘Love,’ writes Violette Leduc in Mad in Pursuit, her 1971 memoir of obsessive love for Simone de Beauvoir, ‘is a word without meaning when I am talking about her.’ She goes on: ‘It’s as though I were to say “spring water” instead of “ground glass”.’

Simone de Beauvoir replied to Leduc’s declaration of love with a prudent acknowledgement that she herself feels ‘colossal indifference’ for Leduc’s affections. Simone de Beauvoir writes in a letter: ‘This feeling can no more embarrass than flatter me. It belongs to your life. You have control of it.’ Simone de Beauvoir’s own life, she tells Leduc, ‘lies elsewhere.’ They would still see each other and be friends, but there would be no romance. Instead, they would meet at the cafe every two weeks and talk about writing, as usual.

‘I could never have,’ writes Leduc, ‘imagined so much frankness in reply to my unbridled sentimentality.’ Simone de Beauvoir’s cool and compassionate response allows Leduc to fall even more deeply in love with love itself, totally permitted to love as passionately as she wants without ever being burdened by being loved in return. Leduc’s account of this perfect love that foments literature is one made of beautiful exclusions:

‘I don't love her like a mother, I don't love her like a sister, I don't love her like a friend, I don't love her like an enemy, I don't love her like someone who is absent, I don't love her like someone who is always near to me. I have never had, never will have a second's familiarity with her. If I didn't know I was going to see her every two weeks, the darkness would swallow me. She is my reason for living, even though I am not part of her life.’

With her beloved’s unequivocal boundary-setting, Leduc’s love is directed toward its proper target, which is writing.

Literature is the place in which Leduc’s beloved who just happens to have the name Simone De Beauvoir is called into being, and it is only in Leduc’s own writing that Leduc can be near to her love. Simone de Beauvoir exists as herself, but also as something else inside Leduc’s famous exercise books full of crushes. And believing in the project made of this epic and unrealisable love, part of how Simone de Beauvoir exists outside of the notebooks, too, is as a literary comrade encouraging that the inside of these books get filled, even if it must be with her own name in place of any Beatrice’s. These are two writers who, like most writers with genius, know that although they are writing in Paris, their real home is and forever will be Carthage.

It’s like Jean-Jacques Rousseau writes in his Confessions in the 1760s: ‘I have, perhaps, tasted more real pleasure in my amours, which concluded by a kiss of the hand, than you will ever have in yours, which, at least, begin there.’

Anne Boyer is a U.S. poet and essayist. She is the inaugural winner of the 2018 Cy Twombly Award for Poetry from the Foundation for Contemporary Art, and the author of A Handbook of Disappointed Fate (UDP, 2018), Garments Against Women (U.S., Ahsahta, 2015; U.K, Mute, 2016), My Common Heart (Spooky Girlfriend, 2011) and The Romance of Happy Workers (Coffee House, 2008). Her next book, The Undying, is forthcoming from FSG in 2019.

That Obscure Object

November, 2018

On desire and its objects in two essays, a short story and three poems. Featuring illustrations by Ana Kirova.